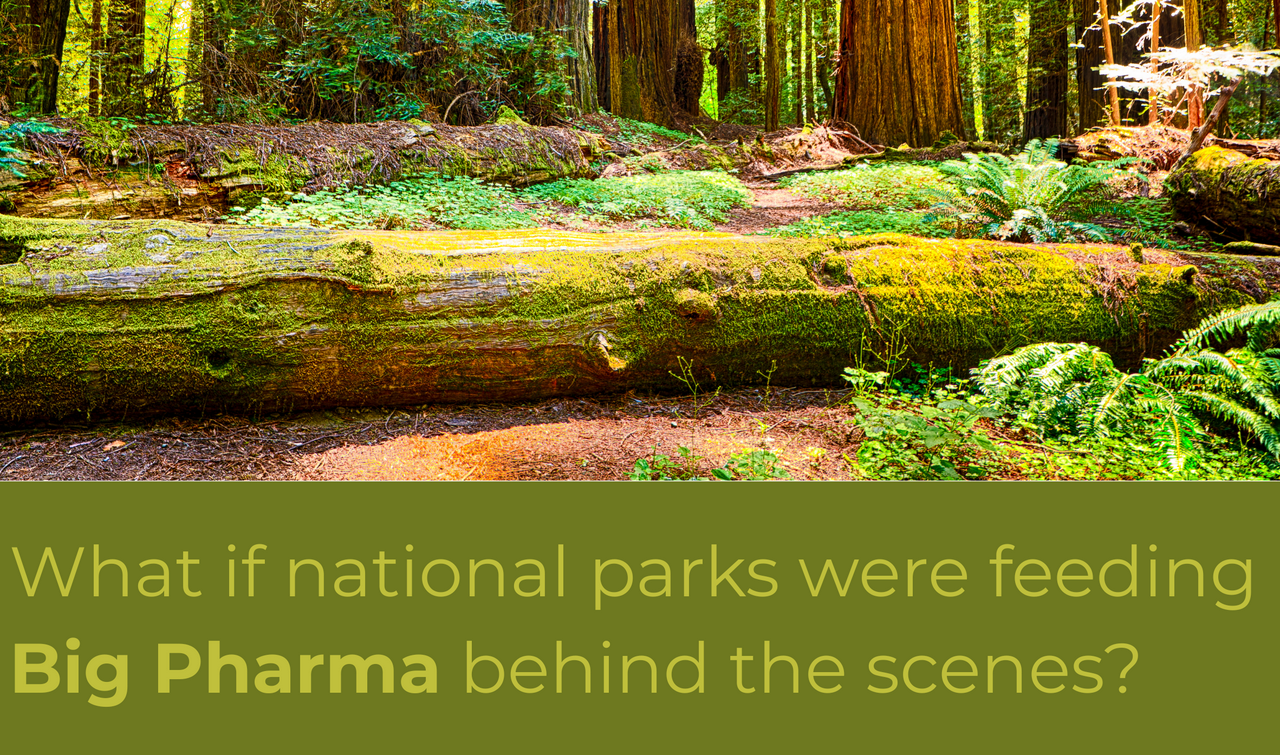

When we think of national parks, we often imagine preserved landscapes, public hikes, and postcard-perfect views of untouched wilderness. We’re taught they exist for recreation, conservation, and the protection of endangered species. But beneath the surface lies a less discussed reality: national parks are also valuable biological treasure troves quietly feeding one of the most powerful industries in the world—pharmaceuticals.

Nature’s Pharmacy: A Billion-Dollar Pipeline

More than 50% of pharmaceuticals on the market today are derived from natural sources. The World Health Organization reports that over 80% of the global population relies on traditional plant-based medicine for primary healthcare. Compounds discovered in plants, fungi, and microorganisms have led to breakthroughs like:

- Paclitaxel, an anti-cancer drug derived from the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia), found in forests once protected under federal land.

- Artemisinin, a Nobel Prize–winning malaria treatment sourced from the sweet wormwood plant (Artemisia annua).

- Penicillin, derived from a fungus, revolutionized modern medicine—and countless related antibiotic compounds have been discovered in remote environments.

Protected areas like U.S. national parks and global conservation zones are often biodiversity hotspots, making them prime locations for what’s known as bioprospecting—the search for novel organisms and compounds that can be used in medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

Bioprospecting or Biopiracy?

Here’s where things get ethically complex.

Bioprospecting is often conducted through research partnerships with universities or government programs. But the line between exploration and exploitation is thin. Critics use the term “biopiracy” to describe the extraction of biological resources without fair compensation to local communities or the public.

A stark example: the Hoodia cactus, used by the San people of Southern Africa as an appetite suppressant for generations, was patented by the South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research—without initial acknowledgment or compensation. Only after international outcry was a benefit-sharing agreement arranged.

Similarly, national parks around the world—often carved out of Indigenous lands—have become repositories of traditional ecological knowledge, while the people who sustained these environments for millennia are displaced or criminalized under conservation laws.

U.S. National Parks and the Pharmaceutical Pipeline

Although the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) is not in direct partnership with pharmaceutical companies, its lands are used by researchers studying natural compounds, often under academic or federal grants. These compounds can later be developed into patented drugs, sometimes by private pharmaceutical companies—with profits rarely returned to the public whose tax dollars fund the park system and research infrastructure.

For instance:

- The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Natural Products Branch has collected samples from U.S. parks and forests for decades, screening thousands of organisms for anticancer and antimicrobial properties.

- Federal databases like the USDA Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database catalog thousands of plants—many found in national parks—with potential pharmaceutical use.

Once isolated, these compounds often enter private hands via patent systems that lock access behind paywalls, despite being drawn from publicly protected ecosystems.

Pharmaceutical Patents: Privatizing the Commons

This raises a core philosophical and political question: Should pharmaceutical companies profit from compounds found in protected lands without returning value to the public?

The patent system allows exclusive control over synthetic versions of natural compounds or their applications, effectively transforming public knowledge into private capital. According to the United Nations, less than 1% of the revenue generated from drugs developed through bioprospecting is returned to source countries or communities.

This is not just about ethics—it’s about ownership of natural intelligence. Who benefits when life forms evolved over millions of years are turned into billion-dollar drugs?

Toward a Just Biological Future

We are entering an age where genetic, ecological, and AI-driven intelligence are converging. In that context, the management of biological resources—especially in protected areas—deserves public scrutiny.

- The Nagoya Protocol (2010), under the Convention on Biological Diversity, was created to address these imbalances by requiring “access and benefit-sharing” (ABS) from biological research. But the U.S. is not a signatory, and many countries struggle with enforcement.

- Indigenous-led conservation and Land Back movements are pushing for a rethinking of protected areas—emphasizing stewardship over control.

The Real Question: Who Are National Parks For?

National parks were created under a noble idea: to protect natural beauty for future generations. But we must ask: Are they still serving that purpose, or are they quietly subsidizing global industries under the guise of public good?

The reality is this: national parks are not just scenic retreats—they are also silent players in the global bioeconomy.

It’s time to rethink how we value these spaces—not just as ecosystems to be preserved, but as repositories of natural intelligence that must be governed with transparency, equity, and integrity.

Sources & References:

World Health Organization. “Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023.”

Newman & Cragg. “Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Last 40 Years.” Journal of Natural Products, 2020.

National Cancer Institute, Natural Products Branch.

U.S. National Park Service: Research Permit and Reporting System.

Convention on Biological Diversity. The Nagoya Protocol.

Vandana Shiva. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge.

🍺 Enjoying the insights?

Buy me a beer & keep the intel flowing:

🍻 Buy Me a Beer.

1/

We think of national parks as sacred public lands—preserved for hiking, wildlife, and future generations.

But there’s an overlooked layer…

1/

We think of national parks as sacred public lands—preserved for hiking, wildlife, and future generations.

But there’s an overlooked layer…